by William D. Parry, CCC-SLP

Copyright © 2022 by William D. Parry

What are stuttering blocks and how can we stop them? Although much has been written about various aspects of stuttering, researchers have not adequately studied or explained the underlying components of stuttering blocks. Therefore, to better understand the cause of stuttering blocks and how to deal with them, we must go beyond the published research. We must fill in the gaps with our own “working hypothesis” based on existing scientific knowledge of neurology and physiology, together with our own observations and experience. The result is the Valsalva Hypothesis, upon which the following explanations are based.

What Is a Stuttering Block?

A stuttering block is an involuntary interruption in the flow of speech that prevents a speaker from voicing a word or syllable. The blockage of words begins in the brain rather than the mouth, as evidenced by the fact that persons who stutter often feel that an upcoming word contains a “brick wall,” even before they try to say it. The familiar manifestations of stuttering behavior – including forcing, repetition, or prolongation of certain consonants – are struggle responses to the underlying block. Although many people assume that stutterers have trouble saying initial consonants, persons who stutter are usually able to form the consonants reasonably well – even when forcing, repeating, and prolonging them. Their real problem is unreadiness to voice the vowel sound that follows.

What Causes Stuttering Blocks?

Before we can stop stuttering blocks, we must understand the underlying forces that cause them. Simply trying to change our superficial struggle behaviors – such as forcing, repetitions, and prolongation of sounds – usually results in unnatural-sounding ways of speaking that quickly fall apart when they are most needed. Rather than trying to control our speech, we must learn how to control the forces that interfere with our speech.

Before we can stop stuttering blocks, we must understand the underlying forces that cause them. Simply trying to change our superficial struggle behaviors – such as forcing, repetitions, and prolongation of sounds – usually results in unnatural-sounding ways of speaking that quickly fall apart when they are most needed. Rather than trying to control our speech, we must learn how to control the forces that interfere with our speech.

At the core of stuttering blocks is an interference with the brain’s motor program for phonating the principal vowel sound of a word. This is the loudest part of the word, without which the word cannot be spoken. Suppression of the vowel sound may be caused by stress hormones triggered by the brain’s amygdala as part of a fight-flight-freeze response and influenced by psychological factors. When speech does not involve phonation, such as in whispering, blocking on words rarely occurs. Conversely, stuttering blocks do not occur when singing, because the person’s intention is to voice the melody – which is carried by the vowel sounds.

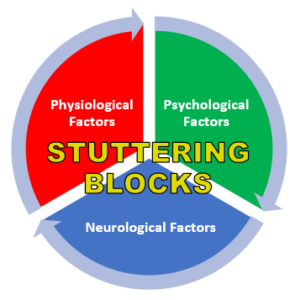

There is no single factor that would explain all the variability and paradoxes of stuttering blocks. Instead, they are influenced by an interaction of three sets of contributing factors – psychological, neurological, and physiological.

Neurological Factors.

There is a growing body of evidence that persons who stutter may have various underlying neurological deficiencies compared to non-stutterers, as indicated by brain scans and other scientific studies. However, such deficiencies alone would not necessarily cause stuttering blocks. Nor would they explain why stuttering severity can vary greatly depending on the speaking situation, or why many persons who experience stuttering blocks are relatively fluent most of the time. Such neurological weaknesses could simply make stutterers’ brains less efficient in processing speech, thereby making the person’s speech processing more susceptible to interference. Therefore, stuttering blocks may not be caused by a lack of ability to speak, but rather by an interference with the natural speaking ability the person already has.

The Role of the Amygdala.

The interference with stutterers’ speech processing can be attributed to the amygdala – a part of the brain that stores fearful memories. The amygdala’s primary role is to help us respond quickly to potential danger by triggering the release of stress hormones, thereby initiating what is known as the fight-flight-freeze response. This is a defensive reaction that we share with the animals, and which has protected our human ancestors for hundreds of thousands of years. When we are confronted by an enemy, the stress hormones prepare us to fight harder to defend ourselves, to run faster to escape danger, or, when neither of these options are feasible, to freeze in place to make ourselves less noticeable.

The amygdala’s function can be illustrated by this hypothetical example: Imagine a prehistoric man on the plains of Africa who suddenly sees a lion. If the lion were to attack, he couldn’t very well fight the lion or outrun it. Therefore, his amygdala triggers a freeze response so, by not moving, the man would be less likely to be seen. Furthermore, the stress hormones would suppress his vocalization to prevent the lion from hearing him. Meanwhile, the man instinctively holds his breath to build up air pressure in his lungs, thereby stiffening the trunk of his body in case the lion attacks.

Persons who stutter may experience similar reactions in speaking situations. Unfortunately, when the amygdala intervenes by triggering a fight-flight-freeze response, the usual result is a stuttering block.

Just as in our man vs. lion analogy, one of the effects of the freeze response is to suppress vocalization. In this case, the stress hormones interfere with the brain’s motor program for phonating the vowel sound – which is the loudest part of a word or syllable and therefore the part most likely to be heard. In multisyllable words, this is the vowel sound of the stressed syllable. We will call the loudest vowel sound in a word the key vowel sound. We are referring to the actual sound that you hear and not the written letter. Without a motor program for phonating the vowel sound, the word cannot be spoken. As a result, we may feel that saying the word is blocked as if by a “brick wall.”

In place of vowel phonation, the stress hormones may substitute a strong urge to exert physical effort on the consonant or glottal stop that precedes the vowel sound. This “effort impulse” often feels like a matter of life or death. This is understandable because, in physically dangerous situations, obeying the amygdala may save one’s life.

Physiological Factors.

As part of the fight-flight-freeze response, the man in the lion example instinctively holds his breath to defensively stiffen his body in case he is attacked. A similar build-up of air pressure may be associated with stuttering blocks. In this case, persons who stutter feel that they are trying hard to force out the word, as if it were a physical object. However, what they are actually doing is a Valsalva maneuver, which makes the block even stronger.

The Valsalva maneuver is a natural bodily function that helps us exert strenuous effort more efficiently. It may also help us force things out of the body (such as bowel movements). It is performed by a neurologically coordinated team of muscles throughout the body, called the Valsalva mechanism. After we inhale, our chest and abdominal muscles squeeze to increase air pressure in the lungs. The air pressure stiffens the trunk of the body so that our arms and legs have a stable base on which to operate more efficiently. Meanwhile, our upper airway instinctively closes to keep the pressurized air in the lungs. In the usual Valsalva maneuver, this closure is performed by “effort closure” of the larynx. However, when the Valsalva maneuver is activated in speaking, the lips or tongue may be recruited by the Valsalva mechanism to perform the same function. Because the muscles involved in a Valsalva maneuver are neurologically coordinated, the greater the air pressure becomes, the tighter the larynx or mouth automatically closes.

How Forcing Perpetuates Blocks.

The speaker’s inability to voice the vowel sound may trigger an overwhelming urge to exert physical effort in an attempt to “force out” the word or syllable. The effort usually focuses on the consonant that precedes the blocked vowel sound while squeezing the chest and abdominal muscles to build up air pressure in the lungs. In words starting with vowel sounds, the effort may focus on the preceding glottal stop, resulting in tight closure of the larynx.

The more the speaker builds up air pressure to force out the word, the more strongly the lips, tongue, or larynx automatically close to resist the air pressure. The forcing may be continuous, or it may result in forceful repetition of the preceding consonant or glottal stop followed by a schwa instead of the actual vowel sound. In addition, the speaker’s delay invoicing the vowel sound may result in prolongation of certain consonants.

Persons who stutter may subjectively feel that they are trying hard to force out a word, as if it were a physical object. However, their exertion of effort actually makes the blockage stronger by restricting the outward flow of air. Attempting to force will continue to prevent voicing of the word unless or until the “effort impulse” is discharged. Speakers then may be left with the false impression that using effort ultimately helped them get the word out. This erroneous belief may reinforce and perpetuate this behavior in the future.

Stuttering Behaviors.

Many outward stuttering behaviors are actually struggles to avoid, hide, postpone, or break through stuttering blocks. In addition to forcing, these may include repetitions, prolongations, insertion of extraneous words or sounds, and even bodily movements. As a result, listeners may erroneously define “stuttering” in terms of these superficial behaviors, whereas the underlying experience of persons who stutter is being blocked from saying words. Many current therapies encourage clients to “stutter” openly and even voluntarily – in other words, to practice what are actually struggle behaviors.

Persons who stutter often sense in advance that an upcoming word is blocked, even before they try to say it. They may then try to hide the block by struggling through it silently or, when possible, by substituting words to which the block is not attached. This strategy is often referred to as covert stuttering.

Psychological Factors.

One of the maddening characteristics of stuttering blocks is their variability. For example, a person might begin telling a joke with perfect fluency and then suddenly block on the punch line. A person may have no trouble saying a word in one situation but then block when saying the same word really matters. This phenomenon may be understood by considering the way in which various psychological factors affect the amygdala’s sensitivity.

The term “psychological factors” does not suggest that stuttering is caused by mental illness or emotional disturbance. Instead, these factors may include a person’s negative beliefs, memories, fears, anticipation of difficulty, and intentions concerning speech. For example, persons who stutter commonly enter a speaking situation feeling that it is very important to make a “good impression” by trying hard not to stutter. Such factors may put the amygdala on high alert for words and situations that it associates with stuttering. As a result, the amygdala may treat an upcoming word as if it were a physical threat and trigger the release of stress hormones, resulting in a stuttering block.

How Can We Stop Stuttering Blocks?

There have been many different approaches to stuttering therapy through the centuries, based on the then-current theories of causation. Early therapies have involved surgery to the tongue, mechanical devices in the mouth, metronomes, speaking exercises, and various forms of psychotherapy. More recent therapies have tried to change external stuttering behaviors through “fluency shaping,” “stuttering modification,” or reliance on electronic devices. Because these methods have failed to produce satisfactory long-term results, many therapists have abandoned the quest for “fluency” in favor of so-called “acceptance therapy.” Persons who stutter are told to accept their stuttering, to stutter openly and proudly, and even to stutter voluntarily.

These therapies have had limited success because they fail to address all three underlying components of stuttering blocks. Based on the understanding provided by the Valsalva Hypothesis, Valsalva Stuttering Therapy is designed to control the factors that interfere with speech on all three levels – psychological, neurological, and physiological.

The following are the main principles taught by Valsalva Stuttering Therapy:

The following are the main principles taught by Valsalva Stuttering Therapy:

Change your negative beliefs, attitudes, and intentions about speaking and stuttering. Your goal should not be “fluency” per se but rather easy and effortless speech. Instead of trying to make a “good impression” by being fluent, focus on your role and purpose in speaking. Instead of trying to please your listener, focus on your own enjoyment in expressing yourself through the music of your voice. Any thoughts about being “fluent” are likely to activate your amygdala and result in stuttering blocks.

Understand the mechanics of speech. Speech begins by inhaling air into the lungs. When the muscles of inhalation relax, air flows up the windpipe and into the larynx (or “voicebox”). There the vocal folds come together and are caused to vibrate by the outflowing air. This is called phonation. No muscular effort is involved; it is all done by the relaxed outflowing air. Therefore, trying to use effort to force out a word will only choke off the airflow. Meanwhile, a little muscle called the cricothyroid adjusts the pitch of the vocal folds, giving melody and inflection to your voice.

The result is a vibrating column of air that sounds like a melodic buzz. The buzz is turned into specific vowel sounds by the shape of your oral cavity, as determined by the position of your lips and tongue. By continuously moving, the lips and tongue add consonants. In this way, the vibrating column of air is turned into a sequence of symbolic sounds. These sounds travel from your mouth into the air, where they are picked up by the listener’s ear. If the listener knows your language, his or her brain will automatically decode the sounds into words and meaning.

Strengthen your motor program for voicing the Key Vowel Sounds of words and phrases. This will reduce the likelihood that stress hormones will interfere with your vowel phonation. Practice “Key Vowel Preparation” with exercises including “Preliminary Vowel Voicing” and “Preliminary Vowel Shaping.”

Learn to discharge the “effort impulse” without struggling. This can be done by gently tensing your puborectalis muscle at the beginning of inhalation. The puborectalis muscle is a part of the Valsalva mechanism which forms a sling around the bottom of the rectum in the pelvic region of your body. By tensing the puborectalis, you can divert the effort impulse away from your mouth or larynx and discharge it inconspicuously.

Relax your Valsalva mechanism while exhaling and speaking. This can be done by slowly relaxing your puborectalis and abdominal muscles while exhaling. Because both of these are neurologically coordinated parts of the Valsalva mechanism, relaxing them will prevent the occurrence of a Valsalva maneuver.

Practice slow, Valsalva-relaxed breathing. Almost all the muscular effort in respiration occurs while we inhale – which is when we are not speaking. Exhaling only requires relaxation of all the muscles that were used for inhaling. Speech is produced on the outflowing breath and is therefore powered by relaxation.

Treat speech as melody and movement instead of “things” to be forced out of the body. When you treat a word as if it were a physical object, it is no longer a word. It is no longer communication. It is simply a useless display of physical effort. Valsalva Stuttering Therapy includes exercises that promote the processing of speech as melody and movement. These include:

A full explanation of the Valsalva Hypothesis and Valsalva Stuttering Therapy can be found in the Ultimate Expanded Fourth Edition of my book, Understanding and Controlling Stuttering (2021).

A licensed speech-language pathologist, offering Valsalva Stuttering Therapy by video conferencing over the Internet (depending on location and subject to applicable law).

Valsalva Stuttering Therapy is a new approach to easier speech by controlling the physiological mechanism that may contribute to stuttering blocks, together with psychological and neurological factors. If you are interested in therapy, send an e-mail to stuttertherapy@aol.com to inquire about a free consultation.

The Ultimate Expanded Fourth Edition of Understanding and Controlling Stuttering (2021) is now available from Amazon. You can check it out here.

You may also purchase the book from the National Stuttering Association and help support the NSA.

E-mail: info@WeStutter.org

or download a PDF version here.